AI, Authenticity, & the Future of 3D Cultural Heritage

Challenges and opportunities for GLAM in a world of AI-generated content.

The rapid advancement of generative AI and the burgeoning development of metaverse platforms present both exciting opportunities and significant challenges for the spatial heritage sector. As tech companies increasingly populate these new digital frontiers with 3D content, a critical question emerges: what is the role and value of authentic, meticulously curated 3D data from our cultural institutions?

This article explores the complexities of integrating genuine cultural assets into environments often dominated by AI-generated lookalikes, examining the responsibilities of GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums) organizations and tech developers in preserving the integrity and contextual richness of our shared digital heritage.

Emerging Concerns: AI vs. Archive

The challenge of disseminating digitized cultural assets alongside AI generated lookalikes recently came up in the IIIF 3D Community Group Slack channel. Folks are (imo) understandably concerned that audiences on platforms like Meta’s Horizon Worlds—which is currently promoting its generative AI “3D AssetGen 2.0” service for world building—will find it hard to tell computer hallucinated creations from curated archival assets. Maybe worse than that, however, I think some audiences simply won’t care.

One question that follows is “How can the gallery, library, archive and museum (GLAM) sector help make metaverse creators and audiences care about the authenticity and provenance of 3D assets?”.

Considering that I see “cultural heritage” often leveraged by tech companies as a reason their service or platform is worthy (we did this at Sketchfab while I was there), I think its high time the GLAM sector began espousing the value of authentic 3D data, and for tech giants to listen up. It’s an opportunity for the heritage sector to demonstrate the strength of their deep knowledge in relation to the subjects that are being digitised in 3D.

But why should the average user, or even a metaverse creator, prioritize a “curated archival asset” over a readily available, AI-generated alternative that looks convincing enough? The distinction matters profoundly because authentic 3D representations carry an inherent connection to real-world context, research, and human narrative that AI models, by their nature, cannot replicate. When audiences engage with an object that is a true digital counterpart of a historical artifact, they engage with its story, its provenance, and the centuries of human experience it may represent. Opting for expediency over authenticity risks diluting our collective understanding, creating a digital landscape where convincing fakes obscure genuine knowledge and where the deep, nuanced stories embedded in our cultural heritage are replaced by superficial facsimiles. This isn't just about visual accuracy; it's about maintaining a connection to the tangible past and fostering a deeper appreciation for the complexities of history and culture, a connection that is jeopardized if we don't actively champion and make accessible the real thing.

As the lines between search engines and AI chat interfaces are blurring, I think it makes sense to place more value on tagging and flagging the provenance of digital assets, whether they are 3D scans, artistic creation, or AI generated. When a school student can ‘request’ a 3D model of the Rosetta Stone, or Michelangelo’s David, or an ancient Greek pelike from an AI service—how do they know if it’s real or accurate or not?

Don’t get me wrong, I think AI has many useful applications related to digital 3D collections (e.g. data quality assessment, object segmentation & annotation, accessibility interpreters, etc., etc.) but conjuring up caricatures of historic subjects instead of leveraging existing, high quality 3D data from the GLAM sector seems like a missed opportunity. Meta’s Horizon Worlds platform is a potentially huge audience for 3D content and I’d love to see the good work of the culture and heritage field better represented.

Authentic 3D assets are out there…

You don’t have to search too hard to find real historical and cultural 3D assets similar to those that Meta uses in their promotional material. Cultural institutions like National Museums Scotland (skfb.ly/orKCG), The British Museum (skfb.ly/6srQY), and the Smithsonian Institution (3d.si.edu/object/3d/neil-armstrong-spacesuit) [shown above] have all made 3D data available online. Critically, however, the data from NMS is not openly licensed and there is also pretty sparse metadata published alongside the British Museum’s scan of Hoa Hakananai'a.

Metadata

A simple way to move beyond a “3D asset for set dressing” is to supply a basic package of metadata (information about the subject, information about the data itself, how the data was created, by whom, etc.) and link this to the relevant 3D file. In this way 3D data evolves from being a digital twin closer to the concept of a memory twin—something with real-world context that exists to illustrate the human narrative. The complete data package (3D + metadata) then has the potential to be viewed, reused, and referenced wherever an end user engages with it.

An opportunity for GLAM organisations exists to “do metadata well”. Good metadata collection and linking practice should be baked into 3D digitisation & publishing efforts, providing the best possible digital resources for academics, creatives, the general public, and tech companies to enjoy and build upon.

Licensing

To encourage the re-use of cultural heritage 3D data in other fields, it should be made available for re-use under a permissive license, but not every GLAM organisation adopts such an open philosophy. Even some that do make data available under open licenses, choose to curtail the possibilities of re-use by applying (for example) ‘no derivative’ or ‘no commercial use’ clauses to the licenses they apply to 3D data. There are sometimes good reasons for this but just as often (in my experience) there are not. Either way, if authentic 3D data is to have a chance of reaching certain audiences outside of GLAM-land, they need to be licensed appropriately.

One reason that Meta might be more interested in AI generated 3D assets is that they—presumably—don’t have to worry about such licensing issues or legal entanglements.

Ethical issues arising from the generation quasi-cultural assets are another issue, but not something I feel qualified to talk at length on. I have enjoyed following the outputs of Ahmad Mohammed’s research in this area and can recommend looking him up.

Optimisation

I’ve written about the need to optimise 3D data for ease of reuse before, so I won’t go into much detail now. Suffice to say, much of the 3D data being published by GLAM organisations is often unusably heavy, exists in a myriad of mesh and texture formats, and the subject’s scale, position, and orientation within a file are often incorrect.

Rather than try and shoehorn huge meshes and a gazillion different file formats into Horizon Worlds, I can see why Meta prefers to generate their own 3D assets which are, no doubt, tailored to have just the right technical specifications for use in their nascent social metaverse platform.

If you’re interested in some of these topics from a GLAM perspective, there are plenty of resources out there. Here are just a few to get you started:

Interoperability

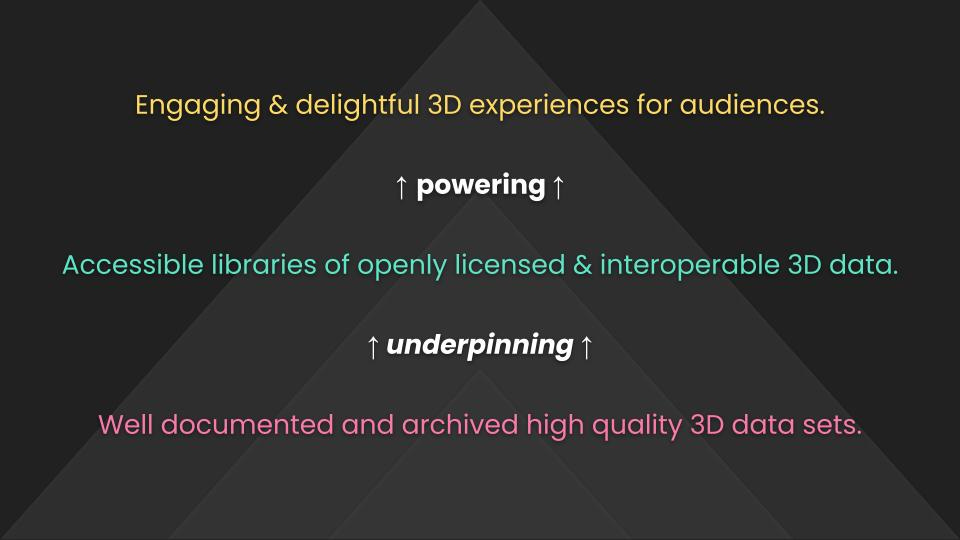

OK, so now you’ve got some great 3D and some great contextual metadata - nice! The next stage is to make the combined data available and interoperable. If you’re not too familiar with the concept of interoperability, the basic goal (in the context of this article) is to ensure that the same 3D data can be easily opened and experienced in different environments e.g. online 3D viewers, metaverse platforms, 3D editing software, etc. In theory, the all the data would be present (3D + metadata) and everything would look the same too (same orientation, scale, material settings, etc.)

The promise of interoperable 3D is to be able to connect GLAM collections data directly with end users, assuming that the platform they are using supports an interoperable specification. The idea is to make it easier for folks in other industries (e.g. education, creative, entertainment, & news) to reference high quality 3D data along with reliable contextual information.

It’s something we’ve been working on for years in the IIF 3D Community Group, and an initial specification for publishing interoperable 3D data online will be launched at the IIIF Annual Conference later this year.

If you’re interested in this topic I can also recommend that you check out:

Proactive championing of good data & best practice

Internally, the GLAM sector is making good progress in the creation and publication of holistic 3D data packages and offering them up for reuse by 3rd parties. There is, however, still lots of work to be done before companies like Meta would choose to engage with GLAM 3D data sets over AI generated simulacrums of iconic historical subjects. My main suggestion to help things along? Make it easy: high quality, well optimised 3D models, accessible APIs, and clear licensing would be a good start.

Looking ahead, there are big opportunities for the GLAM sector (regionally, nationally, globally) to adopt standardised workflows that repeatably produce 3D data that caters to both expert and non-expert audiences. There is also huge potential for the sector to actively engage with big companies like Meta, or Epic Games, or Roblox Corporation, or newer players like VR chat, arrival.space or spatial.io, to champion engagement with authetic 3D data. In both areas, but especially the latter, larger, national GLAM organisations have an opportunity (responsibility?) to lead the way.

Whether you work in the cultural heritage or tech sector, I hope this article has given you some things to think about and investigate. How and where would you like to see authentic cultural heritage 3D data being used in the future? And to what end? Please leave a comment or drop me a message, I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Thanks for this, it hadn't even occurred to me that authenticity goes beyond just copyright, and has a bigger role in heritage artefacts as well.

This is a fascinating read! I have often thought about how AI could assist in provenance research as records are digitized, but the use of AI in creating 3D models has implications for research as well. While 3D imaging captures what is present within the images, as AI creation can only account for what is available within the data at its disposal and what it can predict based on that data (not an AI expert, so someone correct me on this if needed). A model based on predictive outcomes will not be able to uncover new findings, which I think is at the heart of accessibility efforts/the creation of new imaging models (see the ARCHiOx's recent discovery of inscriptions on a medieval manuscript). It has to work in collaboration with the development of other imaging technologies to become and then remain accurate. Even so, your critique about AI 3D models alienating the viewer from the nuances of an object's history remains, as does the current issue of AI models being unable to recreate well know historical artifacts accurately.